A few months ago, I wrote this piece about Reuben Solomon and his Jive Boys, the band headed by a Baghdadi Jewish clarinet player from Burma who trekked to Calcutta during the Second World War and recorded prolifically in India. Two guitarists from the Rangoon outfit, Cedric West and Solomon’s cousin, Ike Issacs, went on to significant jazz careers in the UK and beyond.

A few months ago, I wrote this piece about Reuben Solomon and his Jive Boys, the band headed by a Baghdadi Jewish clarinet player from Burma who trekked to Calcutta during the Second World War and recorded prolifically in India. Two guitarists from the Rangoon outfit, Cedric West and Solomon’s cousin, Ike Issacs, went on to significant jazz careers in the UK and beyond.

A few weeks ago, thanks to Lana Whitney, the Rudy Cotton fan who left a message on this site, I’ve been in touch with Solomon’s wife, Charmaine Solomon – a best-selling cookbook writer who is credited with teaching Australians how to make Asian food. She’s authored 31 cookbooks, among them the very influential The Complete Asian Cookbook, which sold more than a million copies and has been translated in five languages. She also sells a range of spice blends and marinades – the intriguing Reuben Solomon’s Roasted Chilli Jam, among them.

Reuben Solomon was born in 1921 and died three years ago in Australia. But a few years before his passing, he told his wife the story of his life. Over the last week, she’s patiently transcribed it for me. Here’s Reuben Solomon’s amazing story, in his own words:

“I remember the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936. Shortly after that we returned to Rangoon as, with Dad’s deteriorating health and circumstances, they could not afford boarding school fees. We no longer lived in the elegant three-storey house in Godwin Road, but in a much more modest home in Keighley Street. I finished my schooling in Diocesan Boys School in Rangoon. That was the year I started learning clarinet – and old, battered, metal instrument (ex-Army issue) which was, to say the least, not easy to learn on. But once I had blown my first note, I was hooked. This sound became more important to me than anything else. I would practice for hours each day, until sometimes my lips would bleed.

At that time we would get together with nephew Ike Isaacs and brother Saul and a few professional musicians and try to emulate the sounds of the Hot Club of France, sans violin. We had a group called the Jive Boys, comprising my nephew Ike Isaacs, my brother Saul and Cedric West on guitars, Paul Ferraz on bass and myself on clarinet and sax. We used to broadcast on All India Radio in Rangoon, as in those days Burma, India and Ceylon were considered one entity – India. I finished school in 1937 with a pass which meant I could attend University. I did one year of a science degree, but decided it was more to my liking to play music. I remember Ike saying that I was supposed to be studying science but the call of B-flat was too strong. My first job was deputising for a musician in a night club, starting at 10pm and playing until morning – the sun was up when I left. How to stay awake at lectures after such a night?

Gigs in Rangoon included playing with Wally Fagin’s band at the Rangoon Gymkhana Club and wherever a live band was needed. In spite of my tender years, I managed to get quite a lot of work. The earnings came in useful to supplement the meagre allowance Mum received from her brothers. Dad died in 1938, at the age of 61.

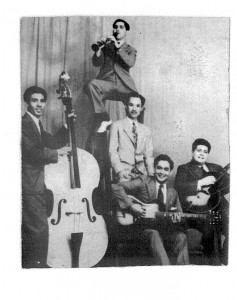

Paul Ferraz (bass), Reuben Solomon (clarinet), Dean Wong (vocals), Cedric West (guitar), Ike Issacs (guitar)

Early in 1939, I did a two-week stint at the Captain’s Retreat, a night club-cum-house of pleasure. The wily manageress offered me contra. I guess I was too naive and settled for money instead.

I am grateful that World War II disrupted life as I knew it – or I might still be living in Burma, and a worse fate would be difficult to imagine. It did take a few earth-shaking events to uproot us. On December 23rd and 25th of 1941, Rangoon experienced some of the worst air raids and bombing. Sirens wailed. After a short time the all-clear sounded and then, when people had emerged from their shelters, numerous planes came by, strafing the people with machine gun fire.

Archie Liddy, a friend of the family who lived just across the road, rushed over to our house after the first all-clear, and said he was going to see whether his girl friend who lived on the other side of tow, was all right. I said to Mum who was in the slit trench with the household servants, “Stay in the trench, Mum. The wardens don’t seem to know whether the air raids are starting or finishing.”

Archie and I drove off in his little car towards Dalhousie Street, and even as we did so we saw Burmese and Indians out in the streets, pointing at the small planes which were approaching, obviously believing they were British planes. We saw people being cut down. Realising the danger but having nowhere to shelter, we had to keep on driving and when we got to Archie’s friend’s house, we just dived inside and under a table. Almost immediately, there was a frightening crash as the house next door got a direct hit. Since the walls of the houses were formed of wooden slats, the force of the blast caused the slats to separate and flashes of blinding light to come through – a sight I still remember.

The Japanese were advancing from the south. Saul and I decided it would be prudent to move mother from Rangoon and leave her with our brother Maurice and his wife Babs in Yenangyaung. This was further north, an oil town of considerable importance to both the British and the Japanese, which meant it was less likely to be bombed. I left Mum with them in January 1942 and returned to Rangoon. There was still music work to be had. With hindsight, it was rather like the band playing on the deck of the Titanic. Japanese air raids increased, claiming more casualties. Our sister Seemah and her family left Burma for Calcutta on one of the last boats leaving Rangoon.

Communications between Rangoon and Yeningyaung were impossible, and Saul and I had no inkling that mother was gravely ill. I noticed that things were taking a turn for the worse, with animals set free from cages in the zoo. I decided it was time to go, but waited until Saul returned from a trip up-river since he had remained with essential services in the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company.

Saul agreed that there was no hope for Rangoon so, taking the family pet, our fox terrier Nessie, we headed for Yenangyaung. When we arrived at Maurice’s house, we had no idea that mother had died the previous day and been buried that morning. Seeing Murice and Babs and Bab’s father Pop, sitting on the floor in traditional Jewish mourning, we pieced together what had happened. Nessie, who had never been to Yenangyaung before, scampered unerringly upstairs to the room where mother had died, and sitting beside the bed, howled piteously. She knew.

A few hours later, Eze (our eldest brother) arrived. He too did not know what had happened, but by some strange coincidence had been drawn there. He had driven all the way from Kunming, China, a trip he was used to as his job was driving lorries with munition supplies for the Chinese army along the Burma road.

This coming together fulfilled a prediction mother had made a couple of weeks before when she said that the whole family would be together and would get out of Burma but she would not be with them. During the seven-day period of mourning, it became obvious that the war was swinging in favour of the Japanese.

My memory for details is not as good as brother Maurice’s, but what I do remember is the fact that we were very fortunate that Saul and I had our musical instruments with us. It probably saved our lives.

On that difficult on month trek towards the safety of India, we came upon more than one tea plantation where English and Scottish planters lived and managed tea factories in the hills of Assam. Starved for music and company, they noticed our instrument cases and would offer us a meal and the shelter of the bungalow verandahs in exchange for entertainment. Other less lucky refugees slept out in the open.

Another incident with my clarinet involved Naga head hunters through whose territory we had to pass. One evening, sheltering for the night under some trees, we noticed that several Nagas were around us, many of them holding their blow pipes. Mischievously, I opened my case and took out my clarinet. Seeing me with this slender pipe-like instrument, they immediately raised their own pipes to their lips, ready to retaliate with their curare-tipped darts. When I blew a few notes and they found that sounds came out, not poisoned darts, there was much hilarity. I realise now that my joke could have had disastrous consequences. What if one uncontrollable Naga had puffed a poisoned dart in my direction? Their chief Head Hunter would have decapitated me and hung the trophy in his doorway!

In Imphal, we were asked to play for an officers’ party. Sustained by relief at having just made it into India (and copious quantities of army issue rum), we played our hearts out. The next day we were loaded onto a truck which took us to Dimapur and then onto a train to Dibrugarh, one of our last stops en route to Calcutta.

As a professional musician in Australia, I sentimentally used that battered old music case to carry my alto sax and clarinet though I had long since upgraded the old army clarinet to a much better Boosey and Hawkes model.

CALCUTTA

Reaching Calcutta on the refugee train, we spent one night in Loreto Convent which had been converted into a refugee receiving centre. Best of all, we were greeted by our sister Seemah’s family and celebrated the passover Seder with them. It seemed fitting that on this most significant night of the Jewish calendar we made it through our Exodus and into what seemed like the Promised Land.

Details of our trek are in Maurice’s story, coaxed from him by Charmaine. She is convinced of the value of writing down family stories, because she says, our children and their children must know their roots.

Shortly after arriving in Calcutta I joined a band at the Great Eastern Hotel under bandleader Alex Shermansky who encouraged me to add to my repertoire many pieces of classical music. We were required to play these popular classics for patrons during lunches and dinners, as well as dance music at night. The dance music was no problem, but I had no experience of the intricacies of classical music. We were required to play these popular classics for patrons during lunches and dinners. Alex would lend me the sheet music so that I could practice the difficult passages and confound the classically trained musicians who suspected, rightly, that I had no experience in that genre. Thanks to Alex, their raised eyebrows were because suddenly I could play the difficult cadanzas and embellishments I had stumbled over a week before. They could not know the hours I had put into practising. I was nothing if not determined. I am always grateful to Alex for introducing me to the kind of music that has given me the greatest satisfaction to play.

This was followed by a stint at the American Club under Lou Roy Cranwell, a cigar-chomping white American gangster – supposedly reformed, but not reformed enough that he didn’t threaten to shoot Saul and me when we said we wanted to leave the American Club. We had a better offer from the bandleader at the Grand Hotel, a black pianist named Teddy Weatherford. Lou Roy Cranwell twirled the revolver around his finger, calling us bastards for even thinking of leaving, but must have thought better of it because we left under our own steam instead of being carried out. Although he was aware that we were a good group and musicians were hard to replace at that time, he wouldn’t offer us more money to stay.

We earned good salaries playing with Teddy at the Winter Garden Ballroom of the Grand Hotel. Our very talented bandleader, Teddy Weatherford, unfortunately fell victim to cholera and I was asked to take over the 14-piece orchestra .

Fronting a big band meant working long hours entertaining American, British and Australian servicemen. It was lots of fun, especially when fights broke out between the “Allies”. The problem was that the Yanks got much higher pay and therefore could afford to be better hosts to the local girls. The British and Australians resented this, mightily. Often a word or two, or even the entry of a lovely young lady on the arm of an American officer, would cause fists and bottles to fly. I would call out, loudly, “Fighting music, guys!” and we would change abruptly from dreamy dance music to something appropriately spirited, like Offenbach’s Can-Can! At the same time we’d be ducking behind our music stands to avoid flying missiles, all without missing a beat or playing a false note. Even if someone did, no one could have heard it over the prevailing din. I also formed a small group within the big band, called Reuben Solomon and the Jive Boys and recorded popular music for Columbia Records. A number of those heavy black bakelite 78s accompanied us to Australia.

During this time I met and married Bonnie Aspinall, very pretty, a hypnotic hula dancer but, like me, too young. In nine months we had a baby daughter, but almost no conversation. The baby was named Mozelle after my mother.

ENGLAND

The next year, 1946, the war in the Pacific ended. After all the American and English servicemen were repatriated, my nephew Ike Isaacs and I accepted an offer from an English bandleader, Leslie Douglas, to join his Bomber Command Band and tour England on the Empire Theatre Circuit.

That was probably the most miserable year of my life. It was immediately after the war, shortages of food, coal and just about everything else made it as bad as during the war. We almost froze as we drove in an unheated coach from one town to another on a series of one-night stands in freezing theatres that naturally were not drawing crowds. Since we were on a percentage of the door, it meant our earnings were pretty slim.

I remember the excitement when we stopped at farmhouse to spend a night and they actually offered us fresh eggs and bacon. We had not eaten such food in months.

In London we boarded with a Russian lady, a Miss Persoff, who had a habit of putting parsley on everything. To this day, I cannot stand parsley. I recall saying to her one day as we sat at table, “Miss Persoff, I’m so hungry I could eat a horse.” She, glancing at the piece of meat on my plate, said, “You are eating it, Reuben.”

I remember sitting with Ike on the freezing coach, both of us too cold even to get up and ring the bell to alert the driver we were nearing our stop. Since it was always very late when we finished a music gig, we were the only two left on the coach. We’d walk to our rooms in Miss Persoff’s establishment, which was almost colder than it was outside. Exhausted, we’d tumble into bed still in our overcoats. The damp, chill sheets seemed to crackle with cold. All we were willing to divest ourselves of were our shoes. Socks stayed on for much needed warmth.

I could hardly wait to get on the ship back to Calcutta but Ike decided he’d stick it out in England. He was a truly inspired and dedicated guitarist and made a great career for himself both in the UK and internationally, travelling the world with Stephane Grapelli and backing artistes like Frank and Nancy Sinatra.

When I returned to India I got a job at Firpo’s, the top restaurant in Calcutta, playing music in a classical-cum jazz seven-piece group. Firpo’s was owned and run by Italians, but the musicians were mostly Spanish. It was at this time that I studied classical music seriously under the baton of Francisco Casanovas, who was the bandleader at Firpo’s. He was pleased with my progress and persuaded me to join the Calcutta Symphony Orchestra.

While I was away in England, Bonnie and baby Mozelle had moved in with her mother but I was not happy staying in her mother’s house. To my great relief, I was offered a contract in Colombo, Ceylon, by a Russian bandleader, Sacha Borsteinas who had heard me play in London. I accepted with alacrity and joined his nine-piece orchestra, living and working at the Galle Face Hotel, Ceylon’s premier hotel at the time.”

The Lady Who Didn’t Believe in Love by Reuben Solomon and His Jive Boys by tajmahalfoxtrot1

I’ll upload the second part of Reuben Solomon’s story next week. The track atop the piece, Constantly, is from the Marco Pacci collection.

2 comments

Terrfic story Precious nostalgia from a forgotten period of troubled times Indeed the enormously tough passage of so many from Burma to India by foot all the way through Assam is legendary So good that you traced Ms Solomon and the reminiscences have been so beautifully narrated I am looking forward to the next part

Hi

just read the above as I am trying to get a good description of Rangoon on that 23rd Dec 1941

my parents Peter McHarg and Thelma Pereira were living there

my dad rode his motorbike to rescue a few people

I am trying to write something about their experiences

they are still alive -dad is 93 and mum 91

and they did write about their experiences for my records while they could still remember

But now sadly both are rather incapacitated in a Nursing home

they immigrated to Australia after the war and have lived a very abundant satisfying life

thanks

Thel